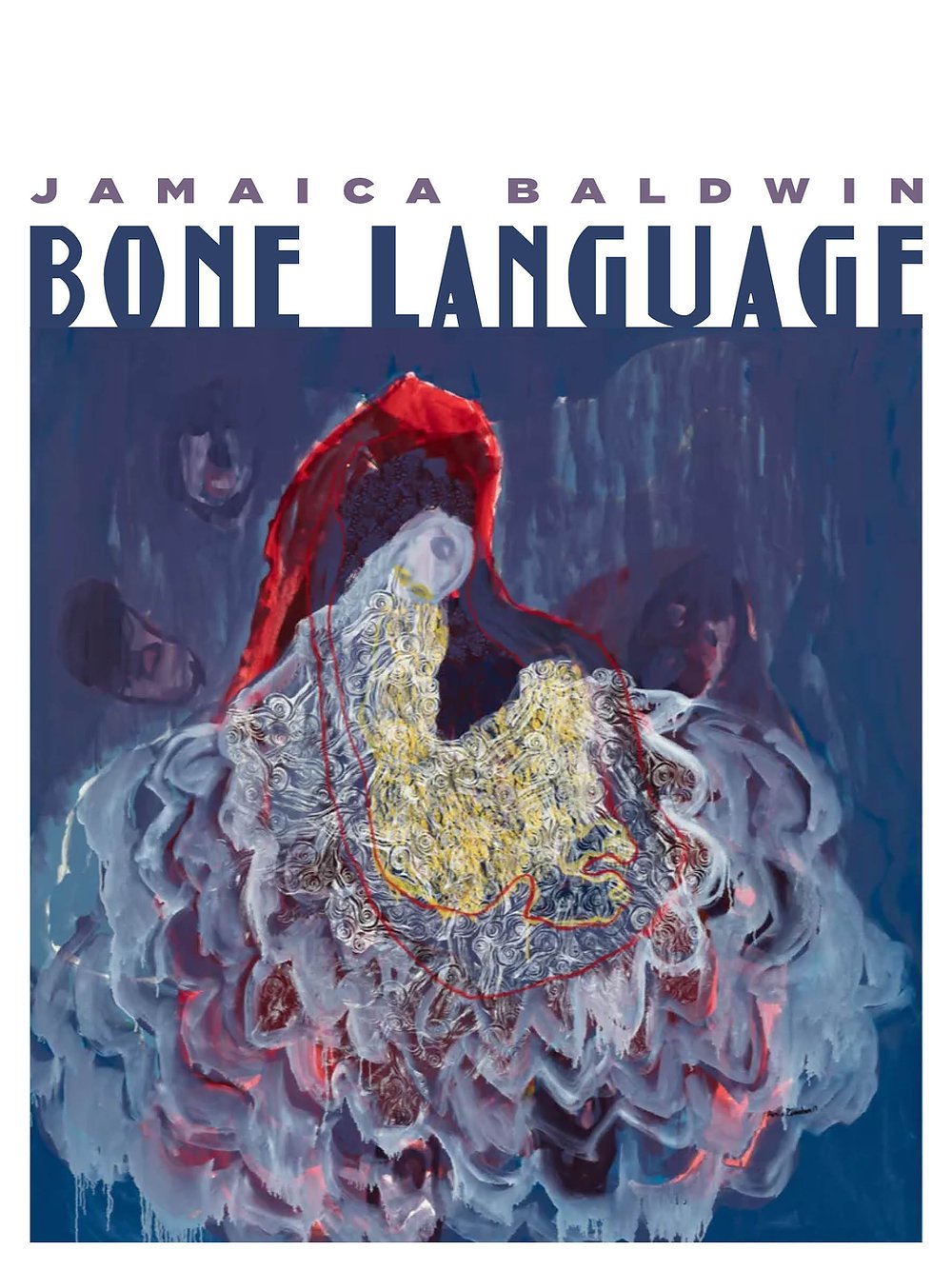

BONE LANGUAGE

About Bone Language

Jamaica Baldwin’s poetry debut, Bone Language, is a testament to the specific ways women survive the world and its attacks on their bodies. At the core of this poet's survival is an engagement with a mother/daughter relationship that lives within the shadows of addiction—a love letter to mothers as they are, not as the world has asked them to be.

With precision and vulnerability, Baldwin’s lyric “I,” signifies her body and its history as it reckons with loss, misogyny, racism, and desire. “I kept answering/your drowned voice with my own, / kept singing along /to our borrowed honey, / kept words, / the dead of women quick / with longing.”

Praise

Jamaica Baldwin turns to bone-truth, skin-truth, and song-truth language. She speaks with a tongue cut on the sadness of her mother and father as she writes "I am a product of their curiosity, their vengeance, their need." Baldwin dedicates "A Cento for Black Women Who Died from Cancer" to Gwendolyn, Audre, Lorraine, Lucille, and June - a breathtaking, heartbreaking list, and so in Bone Language, with lines now writhing and now composed, and ever sensual, she builds a house to heal the body of a black woman after cancer. Healed by the words of these poets, Jamaica Baldwin stands with them in the hospital of her own language. She pronounces words of resistance to the curious and vengeful world: "I am not what anyone thinks I am." Bone Language is, indeed, a beautiful, needful thing.

—Valzhyna Mort, author of Music for the Dead and Resurrected

Baldwin’s magic-flecked collection contains a lament for the inadequacy of dreams in our world. Yet hope is found in her beautiful writing and deeply sophisticated thinking. Her language is spare and her many voices communicate with an arresting strangeness that is at once elegant and disquieting. This is a fine, skilled debut collection by a fully-formed and extremely important poet.

—Kwame Dawes, author of UnHistory co-written with John Kinsella

REVIEWS

To read Jamaica Baldwin’s debut collection attentively is to become aware of how much her poems act inside the instability of language. How much they translate a search for a difference in perception−of her mother, her father, and herself. How much repetition is used to signal identity changes, to unglue meanings, and to anchor in memory and orality what matters. Hers is a speech where signification transborders.